Is Hell Eternal? – Part 2

Against various forms of annihilationism, Part I of this series affirmed the witness of Scripture that unbelievers will suffer eternally in hell. All people will live forever somewhere, yet the destinies of the lost and the saved are vastly different.

While the unbeliever is confined to hadēs, the believer is immediately united with Christ in a place of bliss, known as heaven or paradise. Presently, if a believer dies, he or she will experience what is termed the intermediate state, which is a person’s condition between physical death and the resurrection of the body. The death of the unbeliever confines his or her immaterial being to hadēs. Hell is the eternal and final place of future punishment of those lost without Christ; it should not be confused with the location of the intermediate state of the wicked dead.

The Old Testament Concept of Death

The New Testament provides greater revelation with regard to the concept of death, both for believers and unbelievers. Sheol is the word used most frequently to signify the grave and the location of disembodied souls/spirits, both good and bad. The general meaning of sheol is the place of the dead. The Old Testament does not distinguish between the place where believers and unbelievers go after death. All depart to sheol without any moral distinctions, because the grave is the common destiny. There is no indication of punishment in sheol, because that would be unsuitable in reference to the grave. Yet certainly, the Old Testament does reveal that unbelievers will be punished (cf. Job 21:30; 24:19-20).

Judaism traditionally affirms that death is not the cessation of human existence. The body is placed in the grave after death, and the disembodied spirit is judged before God. Only the righteous enters the place of spiritual reward directly (Heb. Gan Eden, “the Garden of Eden”), while the average person descends to a place of punishment and/or purification known as Gehinnom (Gehenna in the New Testament), but sometimes as sheol. The name Gehinnom is derived from a deep, narrow valley (hinnōm, the “Valley of Hinnom”) to the south of Jerusalem, where children were sacrificed to Molech by the pagan Canaanite nations (Josh 15:8; 2 Kgs 23:10; Jer 2:23; 7:31-32; 19:6, 13-14).

Some Jews regard Gehinnom as a place of punishment and torture, a hell of brimstone and fire. Others understand Gehinnom as a place of retrospection, wherein one recognizes harmful actions and wasted opportunities, thus resulting in remorse. The repentant souls in Gehinnom are punished for a maximum time of 12 months (Yud Bet Chodesh, “the year of mourning”), and then ascend to Gan Eden. Disagreements exists as to the destiny of those who remain wicked; some Jews believe the wicked are annihilated, while others think the soul remains in a perpetual state of conscious remorse.

An antiquated view equates sheol with the New Testament Greek term hadēs, and affirms that sheol had two compartments prior to the cross (until Christ freed the righteous in hadēs and took them to heaven at His ascension). Sheol is typically located as “down” in the Old Testament, and was thus perceived as a subterranean and gloomy place such as the Babylonian underworld or the Hadēs of Greek myths. Another view is that sheol is the place for the bodies of the deceased; that is, the grave. Unlike the present world, sheol is a place of silence (Ps 94:17; 115:17) where there is no praise of God (6:5; 30:9; 88:10-12; 115:17; Isa 38:18). It is a place of inactivity (Eccl 9:6, 10) and sorrows (2 Sam 22:6; Ps 18:5; 116:3), which is not proof of “soul sleep” but rather the lifelessness of the body in the grave. Other verses refer to sheol enlarging its throat, because the grave is where maggots and worms cover the body (Job 21:26; Isa 14:11) and it decays (Ps 49:14). Sheol is unavoidable (Ps 49:9; 89:48). Several verses depict sheol as “beneath” (Isa 14:9); that is, in the lower parts of the earth (Deut 32:22; Isa 14:15). The grave is contrasted with the highest heaven (Job 11:8), probably because ancient burial shafts for the tomb were frequently deep in the earth (yet this is not any indication of a large subterranean underworld).

Several verses in Scripture are important for understanding the destiny of the righteous in death. Psalm 16:10 declares, “For You will not abandon my soul to Sheol; nor will You allow Your Holy One to undergo decay.” The King James Version of the Bible translates sheol as “hell,” though the term does not mean hell in the sense in which it is commonly understood (as in the domain of the wicked or the abode of punishment); rather, it refers to the grave. The idea is that the body would not remain in the grave, but would rise again to life and light. Furthermore, the language does not prove the words used in the Apostles’ Creed that Christ “descended into hell” (cf. Eph 4:8-9), nor does it mean that Jesus personally went to hell for the purpose of preaching to spirits in prison (1 Pet 3:19). For truly at the time of His death, the Lord entered into Paradise (Luke 23:43).

The great chasm that separates Paradise (or “Abraham’s bosom”) from the place of torment in hadēs is likely the heavens themselves. Sheol is best understood as the grave because it refers to the place of the dead. The precise location (heaven or hell) depends upon whether a text refers to believers or unbelievers. Luke 16:19-31 simply indicates that Abraham’s bosom and hadēs are very distinct places. Jesus referred to the rich man only as being in hadēs, whereas Abraham was seen “far away.” The Lord said that “a great chasm” was fixed between the two, so that for one to be transferred to the other location would be impossible. Abraham and Lazarus are seen in comfort, while the rich man in hadēs is “in agony” and requested water to cool his tongue. The dreadful conditions described in Luke 16 are the intrinsic consequences of being confined to hadēs.

The prophetic implications are unmistakable: Lazarus was experiencing the joy of everlasting life (Abraham’s bosom) as a result of his faith, while the wealth of the man who died in unbelief would not protect him from suffering the eternal torments of hell. Luke 16 says nothing regarding the doctrine of limbus patrum or purgatory, where souls are supposed to go when separated from the body prior to their abode in either heaven or hell. Roman Catholicism teaches that limbus patrum is located in the confines of hell, and is said to somewhat resemble Abraham’s bosom. Yet Scripture describes the latter as a place of comfort, which is vastly different from the teaching of either limbus patrum or purgatory. The limbus patrum of Catholic doctrine borders hell, yet Scripture declares that a great chasm separated Abraham’s bosom.

The notion that Old Testament saints were captives in limbus patrum until the Lord’s resurrection, is not conclusive. According to this teaching, when Christ died on Calvary’s cross, He descended into a distinct compartment of hell, released those saints who were captive there, and carried them with Him in triumph to heaven. First Peter 3:18-20 is one of the primary passages quoted in defense of the doctrine of limbus patrum or purgatory, and for those who affirm particular beliefs regarding the circumstances of the dead in the intermediate state.

Peter referred to “disobedient” persons whose “spirits” are “now in prison.” The “spirits” were the antediluvian unbelievers in the time of Noah, who disobeyed God. They were sinners of a most incorrigible type, and manifested their disobedience by rejecting Noah’s preaching. Presently, they are “spirits” because they died long ago and their bodies have not yet experienced resurrection. The spirits of those unbelievers are “now in prison” awaiting resurrection and judgment by God. One could rightly say that Jesus proclaimed a message to Noah’s unbelieving contemporaries in His spirit through Noah (i.e., His spiritual state of life prior to the incarnation). Noah preached a message that God revealed to him, and in this sense, Christ Jesus spoke through him. When Peter wrote his epistle, it was as if Jesus was speaking to their unbelieving persecutors, as the church bore witness for the Lord amid a hostile world. Noah experienced the same type of opposition in his day as Peter’s original recipients did in their time, and as the church does in the present era.

First Peter 3:18-20 cannot by any possibility refer to a “prison” for Old Testament saints, because the antediluvians of Noah’s time were reprobates, not believers. The “prison” cannot be purgatory, because the Council of Trent refers to it as the place where “the souls of just men are cleansed by a temporary punishment, in order to be admitted into their eternal country, ‘into which nothing defiled entereth’” (The Catechism of The Council of Trent, trans. Jeremiah Donovan [Baltimore: Lucas Brothers, 1829] 51). The antediluvian sinners were not just; rather, they were hardened in their unbelief. They are the only ones to whom Christ preached.

Conclusion

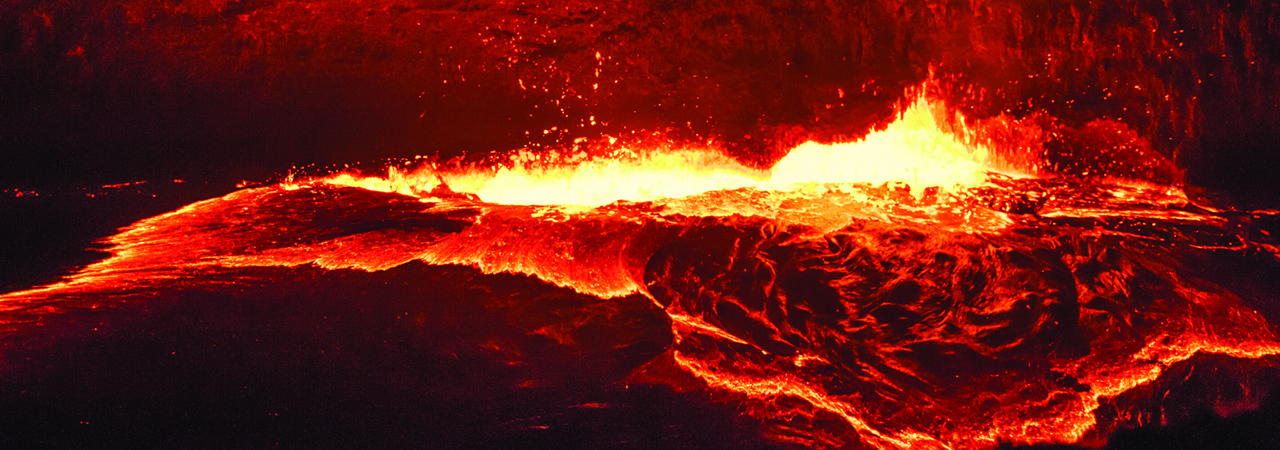

What Christ declared is that—upon death—the ultimate destiny of a person is either heaven or hell. For the believer, the place of blessing is where Abraham is, while the unbeliever will enter the place of torment. The Old Testament frequently indicates the truth of eternal spiritual punishment by fire (cf. Lev 10:2; Deut 32:22; Ps 18:8; 50:3; 97:3; Isa 30:27, 30, 33; Dan 7:10). The concept herein, in addition to the divine pronouncement of “calamity” upon the “valley of Ben-hinnom” for its evil (Jer 19), is the basis for the dreaded name “Gehenna.” The final sentencing of the lost to Gehenna (hell) will not occur until the end of the thousand-year millennium at the “Great White Throne” judgment (Rev 20).

Jesus referred to Gehenna as a place of future punishment (Matt 5:22, 29; 10:28; 18:8-9; 23:15, 33; Mark 9:42-48; Luke 12:5), and the New Testament is emphatic that such judgment is eternal (Matt 25:46; Mark 9:47-48; Rev 14:11). The book of Revelation refers to Gehenna as “the lake of fire” (19:20; 20:10, 14-15; 21:8). The testimony of Scripture is that saints and sinners will continue to exist forever (Eccl 12:7; Matt 25:46; Rom 2:8-10; Rev 14:11; 20:10). The doctrine of annihilation (either of one’s being or consciousness) is contrary to the biblical witness. Furthermore, annihilation is unfitting to be called punishment, since the judgment implies consciousness of one’s doom and torment. Many people who have become weary of life welcome the concept of annihilation as something desirable. Yet all people will live forever in either heaven or hell, and this destiny is based upon their relationship or lack thereof with the Lord Jesus Christ.

Midnight Call - 08/2021